If you’re trying to fit into someone else’s box, you’re gonna end up destroying yourself

Conversation between Maurice Carlos Ruffin, Ash Baker, and Zeke Perkins

Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s debut novel, We Cast a Shadow, follows one father’s quest to protect his mixed race son from white supremacy. Set in the near future, the narrator has made it his mission to erase his son’s blackness through a new technology called “demelanization”. Moving at an electric pace, the book explores fatherhood, racism, gentrification, and a whole lot else. Ash Baker, Art and Digital Media Editor, and Zeke Perkins, Editor-in-Chief, sat down with Maurice in the William T. Young Library at the University of Kentucky to talk about the book.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length. A full version of the interview can be found on the New Limestone Review’s podcast, “I Wanted to Also Ask about Ghosts”.

Ash Baker: You talked a little bit last night at the reading you gave on campus about how it’s hard to put this book into a category. A lot of people want to call it speculative fiction, but it’s not really that. Is it hyperreal? Is it surrealist?

Maurice Ruffin: Is it satire?

AB: Right—is it satire? It’s sort of hard to put it into one of these categories. But we can say that it’s certainly not the world that we’re living in now. So, I guess, regardless of which category it’s placed in, what do you feel this novel’s world teach us in our world, about our world, and how is your book’s world related to this one?

MR: One of the things about the biggest problems in our society—whether it’s racism, misogyny, or transphobia, or any number of other issues—we often feel that when there are large victories, the problem has been solved. So, I remember when I started this book in 2012, Barack Obama was still our president, and there had been a discussion for years about whether or not we had solved the race problem. In my own studies of history, just looking back through American history, I recognized that a lot of our issues are cyclical. We have these sort-of nadirs, and we have these sort-of pinnacles, and we go back and forth. Each generation forgets what happened before. The book is set in the future, but it’s really designed to remind people that the issues of white supremacy, racism, bigotry, prejudice—these things are always running in the background of the American program. I mention the idea of like, racism is almost like an app on a phone. It sort of runs in the background of your phone the entire time. Maybe you don’t always activate it, but it’s there and it’s doing its thing behind the scenes. So, I set the book in the future, but it’s not so farfetched that there’s flying cars. A lot of things that you see in the book are things that we have today, and a lot of [the protagonist]’s experiences are things that you can imagine yourself having. One review—I think it was the Boston Globe—said that the book doesn’t go too far because the ridiculousness of racism in general is so expansive that we’re being surprised constantly. After that review came out, there was that whole issue in Virginia with the blackface. That could happen February of 2019—Black History Month, of all things—and I couldn’t make that up! So, the book is full of those sort of incidents that seem like they are beyond the pale, and yet they fit right into the sort of program of how America works.

Zeke Perkins: From a craft perspective, the book starts at an incredibly fast pace and doesn’t let up. It’s kind of breathless, anxious. The transitions are many times almost hallucinatory—jumping from one place to the other. This book is so much about fatherhood and being a black man in America, wanting to protect a black son, and it felt in some way as if every aspect of this book is more or less taking all the energy of that terror and anxiety, of raising a black son in America, and putting it into the form of this book.

MR: Yeah, I think that’s one hundred percent correct. I think a lot of the energy that the character deals with in trying to navigate racism on behalf of his son and his family I tried to make come through in the text itself. From a practical standpoint, I had a very simple process: In my mind, I see the character as a real person. I found that in order to make the text move very quickly, and to not have any dull parts in it, I would say to the character that it’s like we’re on a plane right now, and you’re trying to get my attention. Most of us, when we’re on planes, don’t want to talk to our neighbor if they’re not, like, with us. And so I said, only tell me the parts of your story that are interesting, and always skip over the boring parts. It’s like Scheherazade. The narrator was constantly pulling out these tales that were designed to keep me focused on what he was saying. I think that it meant that, the things he was saying were never mundane things, never secondary things.

ZP: And there’s a way it breaks from a more realist tradition. Instead, it’s something like a thriller at times. Like Ash was saying earlier, it’s hard to categorize.

MR: Totally. I think we’re lucky to live in the modern era, and we have access to all of the forms throughout history. As a quote-unquote literary writer, I can use genre. I can use speculative fiction and thrillers and mysteries and experimental fiction to inform how this book is built. So, in every scene, not even every chapter, but every scene, I could say, well, what works well right now? What makes this pop? What makes it feel interesting? A thriller is one form of that. There’s a lot of things happening that are mysterious or shocking or strange. He’s responding to those things like somebody in a thriller film might respond to them sometimes.

AB: A huge theme in the book is performativity and masking, face painting. Even in the first chapter, there’s a part that’s really kind of ironic, where he says something like, “I wasn’t a dancer but I danced anyway.” In the world that we live in, people of color are made to perform for white people to make them feel more comfortable, LGBTQ people are made to perform for straight and cis people to make them feel more comfortable. So, I just wonder what your thoughts were in approaching that in the book, and what you hoped to accomplish by using that as one of your central themes, and what you hope people take away from that.

MR: That’s a great question, Ash. I think that part of what anybody who feels othered deals with is, how do you maintain yourself in a space that wants you to be quote-unquote normal? I think that for this protagonist, throughout the book, he is constantly fighting the fact that if he is completely honest, and completely forthright with the people around him, they’re going to try and stop him, or they’re going to call him crazy, or they’re going to try and redirect him. So, he is constantly making these sort of choices in the moment to say well, I’m not going to be my true self, I’m going to say something or do something that gives this person what they want from me in the moment in order to get to my next goal. He’s very goal-oriented in the book. My experience being a black man in America is often performative. One very small thing happened this morning: I was at the gym in the hotel, and there was a lady on the treadmill. So, I walked in, and after like ten seconds, the lady got off and just walked out. Now, I don’t know if that’s because of my presence, or was her routine finished? I have no idea. But I do know that I wasn’t just going to walk in really quickly and hop on the treadmill next to her and start running without her seeing me first—to give her a moment to adjust to me being in the room. Life has taught me that, if I’m in a store, and there’s a store manager and he’s looking at me, I need to make sure that I smile at him. If there’s a policeman in the vicinity I need to make sure that my hands are where he can see them or where she can see them. And I think that a lot of those things inform a lot of black experience, and certainly this narrator’s experience in the book, as well.

ZP: I read this book as a sort of regression story for this unnamed narrator. I thought of The Godfather, actually, and Michael Corleone.

MR: He transforms.

ZP: Exactly, and it sort of traces the trajectory of Italians becoming “White” in America. The irony that, in protecting his family, he destroys his family. This is pretty similar for the narrator in We Cast a Shadow. There’s something about a desire for post-racialist society and the desire to keep this guy’s son alive by basically converting him into a white man — he kind of kills his soul in this narrative.

MR: It’s funny, because, for anybody, if you’re trying to fit into someone else’s box, you’re gonna end up destroying yourself. He thinks his son’s only safety in the world is if he’s a white person, and he’s willing to give anything up for that. You mentioned the idea that he devolves in the text, and I think that’s true, and I think that he probably sees it as it’s happening. He knows that things are falling apart. People are telling him that—his mother says it, his wife says it, his friends say it. I think for him, the goal is too important. He’s willing to take that chance and lose what values he has in his life, as long as the value is not his son. I think that it’s sort of a metaphor for choices that we all make in our lives. You have to decide what’s important to you. We’ve seen it throughout stories such as Icarus flying too close to the sun, Michael Corleone in The Godfather. He starts out this meek college student and becomes the Godfather, essentially. We see it played out because it’s a real thing in the world.

ZP: I think another interesting aspect of this is the violence of a fatherhood. Patriarchy, in a way, of wanting to control everything so as to protect your family.

MR: Ideology. If you believe something in your heart, nobody can change your mind about it. One of the dangers of ideology is that you can’t learn from experience, you can’t learn from people who care about you trying to tell you, ‘hey man, maybe that’s not the best way.’ So, you’re right. Even towards the end of the book, he’s still sort of thinking, ‘this one idea I had is the only right idea.’ There’s almost a religious zealotry to the way he approaches his mission.

AB: There’s this scene in the book where the family is on a tour at a plantation, and Penny and Nigel challenge these tour guides on their history. The tour guides are completely brushing over slavery’s part in the civil war. Penny and Nigel bump up against this. In the book, there’s clearly a rewriting of history happening. People don’t understand history maybe the way that it happened.

MR: It’s a constant struggle. I’m in my forties now. I think a lot of people who are half my age—people in your cohort, basically—what I admire is that many of you are paying attention in ways that my generation did not pay attention. You are putting names and labels on things that people from my generation would’ve said, “oh it’s just a thing that will go away. It’s not a big deal”. I think that, in the book, this main character has a problem in that he sees the fact that racism still exists and he sees his wife Penny call it out in that scene but he’s thinking, “well I could call it out but it’s next going to help me do what I need to do.” The problem is a chess game in the moment. On one hand, I could sit here and call out these racists on the plantation and say, “oh, what they are doing is a problem.” But he’s also thinking, you know, Penny doesn’t quite understand what I’m looking at right here. She doesn’t see the problems that our son, who is half-white and half-black, is facing. He’s already talked about how because he is black and his wife is white – she loves him and, as a former activist, she gets what the problem is but she doesn’t quite get it on a visceral level. Because of that he knows that he can’t just talk her into understanding so he’s making a kind of executive decision to go around her. Penny and Nigel, if you wanna call out the racism in the area, so to speak, then fine enjoy that. I’m gonna lay back here and see how I can get to my goal. He compromises a lot. I don’t think he would make James Baldwin or Maya Angelou proud with a lot of his choices but those are his choices.

AB: There’s something that I was really curious about. The family in the story, they eat a lot of vegetarian stuff, a lot of vegetarian jerky. Are they vegetarians?

MR: Well, meat is murder. One of the things is that the book is set in the future and I was thinking maybe we have evolved more when it comes to things like meat and sustainability so, Nigel, the son who is only like 8 years old, is like, “we can do better in terms of what we consume as human’s in America”. And I think Penny (Nigel’s mom) is more on the fence. And the narrator, he just does whatever they say unless he’s out at a function or at work, then he does his own thing. To a certain extent, Nigel and Araminta [Nigel’s friend], are very evolved and very conscious. I think it’s one of the tragedies that the father is the least evolved.

ZP: Activism and organizing plays a pretty big role in this book, though a conflicted one. There are two examples of groups purportedly standing up for the black community in “The City”. One is BEG, a really aptly named group, which is more less interested in assimilation and a sort of respectability politics. But then we have ADZE, a sort of para-military, “terrorist” organization that ends up causing mostly chaos. Then, at the very end, we’ve got positive example of an alternative life at a commune. But obviously that sort of life wouldn’t be available for most people in the Tiko [the expanding, fenced-in black ghetto in the novel]. I’m interested in how you conceive of social change and writing about activism?

MR: I think part of the book is an exploration. Different modes of being in the world. For me, it was a lot of fun to have this commune in the end where, for these characters, this was a pretty good solution. Then you have ADZE which is, you know, urban and they are paramilitary and they are fighting back literally with weaponry. I don’t know what the right answer is. If I knew that I wouldn’t be writing novels, I’d be writing non-fiction. I’d be saying, “do this thing”. But I thought at least I could give representation to different approaches to the problem. That’s why, I think the characters – and it’s a big cast with something like twenty different speaking characters – with them I wanted to have different view points expressed as much as possible.

ZP: Something that kind of steps outside of this history or context specific questions are these moments of awe in relation to natural beauty. Last night, at the the reading, you talked a little about the universality of the human experience.

MR: One of the things that I think about is how often black appreciation for beauty is not depicted very often. We don’t have very many scenes in movies of black folks looking at stars. And that’s a very universal experience. People have been looking at stars for millennium. I think subconsciously, when he’s in that cave and there’s the star field in front of him, it’s kind of me saying, “you know what, I’ve done this myself and I’ve had friends do it who are black, so just put it there.” You know the main character has this appreciation for aesthetics because his son’s appearance is very important to him. Also, his own looks – he dresses very fancily in the book. I just think that, you know, beauty is somehow related to prosperity and racism is somehow related to economics and those things are part of the same machine that is tryng to work out this equation. Sometimes there are things you do as a writer that are poetry or a formula or an equation and you don’t really know what the answer is so you put the parts there and let the reader put them together in their own minds. And sometimes it creates something that is bigger than the sum of its parts.

ZP: Yeah, I mean the themes in this book are so interconnected: light and dark, white and black, masking and face painting, the dualities are huge and they mean many different things. In the beginning, at a party the narrator attends, even the cat is dressed up as a dog [at one point barking like one].

MR: He’s a trans-species character [laughs].

ZP: With so many character and voices hitting these themes over and over again, in terms putting it together, what was your process?

MR: Well, I think it comes down, in part, to my personal experience in New Orleans having a very big community. There are some cities – LA, for instance, is huge. It’s a gigantic metroplex where you can’t get anywhere without a car. Then there are cities that are very walkable where people know each other’s names. New Orleans is a place where it’s not so big that you can’t know your neighbors and it’s not so small that you are always in each other’s laps. In the book, part of the construction of how the city works is that almost all the characters know each other. And there are very subtle instances of these coincides in the book that are sort of Easter eggs. Like one example is, there’s one scene where the main character is working for BEG and he’s trying to convince white folks to take a pamphlet from him. And the main character mentions that there was a black men killed on the street a few days before and he kind of says, there’s blood on the ground, they couldn’t get it all off the ground – that’s a character that appeared earlier in the book. I don’t wanna get too deep into the Easter eggs but the point is that the characters all know each other and the incidents all effect other. It’s kind of one of those domino-type deals where you know knock over one and it knocks over the next. It goes in circles and circles and circles. Even when you get to the very end of the book, they are things that are happening that are linked to the very beginning of the book.

AB: So, Zeke and I were talking about how much you love Easter eggs and and we were just wondering if you had a favorite Easter egg in the book.

MR: Oh wow. Well, one of the corniest ones is where he’s at the basketball arena, which is called Secret Nine Arena – so Secret Nine is the name of a Negro League baseball team that was sponsored by Luis Armstrong for poor black kids because they didn’t have their own teams so for me there was this joy in this big corporate stadium being named after this almost socialist, very small organization that was made to support poor black kids. But that’s not the one I wanted to get to. In the stadium, when he goes upstairs to box seating they are eating pie. He says if he was to rate it on a scale of 1 to 10, he’d rate it a 3.14, which is obviously the value for pi the number. So there are these really small things that just make me smile while I’m writing.

ZP: We also have to remember they are eating Marionberry Pie – after the former mayor of Washington, D.C., Marion Barry.

MR: So yeah, the pie has multiple meanings. I should’ve had them say something like, “It’s as good as cocaine!” I’m sorry Marion Barry. I didn’t mean it.

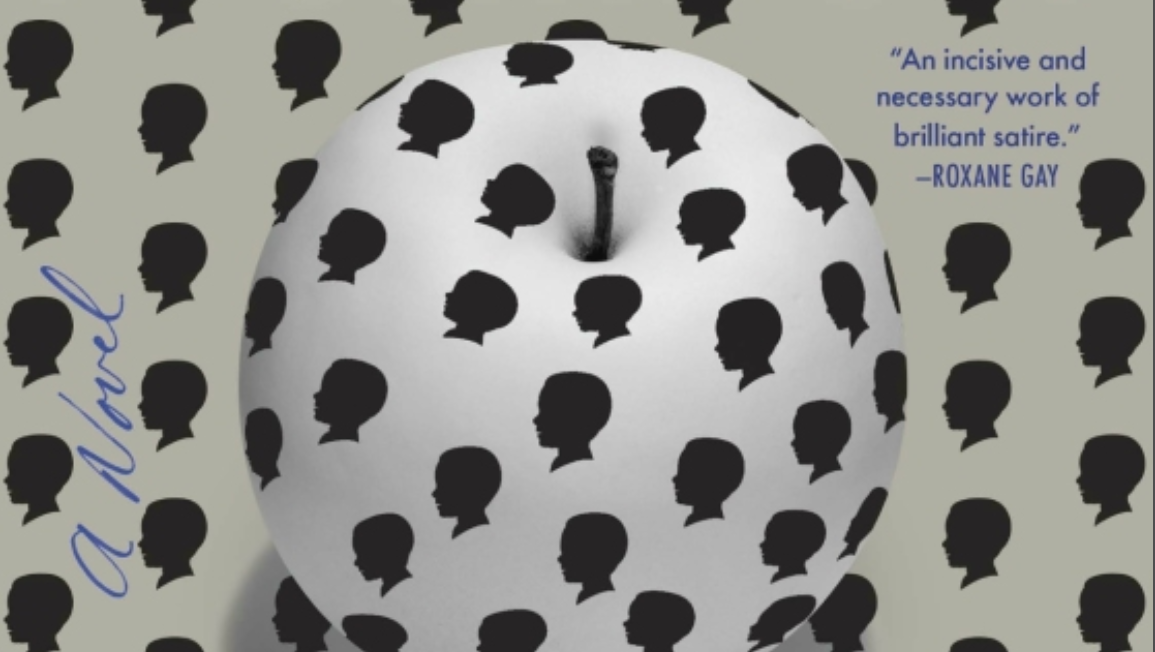

AB: So, you were talking about this off-air, how the cover to your book is fantastic.

MR: So the cover, it’s honestly a work of art itself. The man who made it is Rodrigo Corral. He made the cover for The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by Junot Díaz. He made Jay-Z’s Decoded album cover, the cover for Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club and many other iconic covers over the past couple decades. When I heard his name for mine, I was like “Oh, of course.” And he completely exceeded my expectations. I mean he just created something that—this is what I found out, just yesterday, that people are buying the book in big numbers, but they’re buying it in a higher proportion of physical copies than digital or audio copies than normal. 95% of the buyers want the physical copy because it looks so good. So, they’re just shipping out lots of these books because people want it on the shelf. And I appreciate that because I like it, because it looks really nice.

AB: So, Zeke and I just wanted to ask you some, like random questions that have nothing to do with literary life or anything like that.

MR: Lightning round.

AB: So, we’ve been talking about movies a lot. We all love movies here, and so I just wanted to know if you had a favorite movie of 2018.

MR: Hmm. I will say this: I thought that the 2018 Oscar class was stronger than the 2019 Oscar class, so I had like a lot of favorite movies from ‘17. But for ’18, I probably would have to go with Black Panther. Just because, for me, it was so path-breaking, the idea that you could have a movie that cost a couple of hundred million dollars to make starring a black lead and a largely black cast, giving us these protagonists who control their own fates but a whole new version of what blackness is in the world. I think people really responded. I mean it made a billion dollars, I think because people were tired of seeing the stereotypes of, you know, the African guy in a loincloth; he’s speaking sort of gibberish. This was a vision that has some truth to it because, you know, the actual continent of Africa, I’m sure there are wars going on, but there’s wars in every continent. But there’s also a lot great technology, a lot of great art, a lot of great music, and so this movie sort of brings that truth to the forefront, and of course, it was good-looking, and it was fantastic, and it was very entertaining.

ZP: I wanted to ask about Sorry to Bother You. You met Boots Riley, right?

MR: Yeah, I met Boots Riley back in October. He was the creative director for the New York Times photo shoot, which involved 32 black male writers of our time, and I was one of those 32 writers. I mean, it was amazing to meet him. He just was wonderful. He had on his Oakland flannel, which is sort of like the uniform for that part of the world. But, on Sorry to Bother You, I love that movie so much because it was just so willing to be itself. I mean, it shifts tones throughout from straight, to surrealist, to metaphysical, to, like, blacksploitation almost at times, and my brain was lit up the entire time. You don’t see this every day in film. And I think he should have been nominated for several awards. In my heart, he won the Oscar already.

AB: Thank you so much for coming and hanging out with us and answering all of our questions.

MR: All right, well I’ll be back like Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Maurice Carlos Ruffin has been a recipient of an Iowa Review Award in fiction and a winner of the William Faulkner–William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition for Novel-in-Progress. His work has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, AGNI, TheKenyon Review, TheMassachusetts Review, and Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. A native of New Orleans, Ruffin is a graduate of the University of New Orleans Creative Writing Workshop and a member of the Peauxdunque Writers Alliance.

Ash Baker received their Bachelor’s in English and Cinema Studies from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Ash is an MFA Candidate in Fiction, focusing on short stories, and also a regular contributor to the film podcast and website Cinematary.

Zeke Perkins has spent most of his working life fighting for social justice as part of the labor movement. His fiction, essays and interviews have appeared in HobartPulp, Entropy, Queen Mobs Tea House, and forthcoming in Peauxdunque Review. He is the winner of Peauxdunque Review’s 2018 Words and Music Writing Competition in the short-story category. He lives and writes in Lexington.