I had been just as surprised as one might expect when, at the age of ten, while making breakfast one morning, I cracked open what I thought was a normal chicken egg and found, covered in egg white, a tiny naked man—full head of hair, a Roman nose, strong tightly-muscled arms. So statuesque, lying prone in my mixing bowl.

Fiction by Michael Mau

Mother is calling. She is going to Atlantic City with some friends and can’t leave Cliff home alone. “You know how he is,” she says, and I’m not sure if this is an indictment.

“He’s twenty-eight, Mother,” I tell her. She treats him as if he is still a fragile child.

“He’s on that internet day and night talking to people with one of those telephone operator headsets,” Mother says.

The last time I visited, Cliff had shaved his head and was spending his nights in Aryan Brotherhood chat rooms. He even met a woman, an Italian fascist who did community outreach for the Roman Anti-Zionist Reform Party, the RAZRs. This is all on her Facebook page. “She doesn’t care what I look like,” Cliff had said, “Only what I believe.”

And now Mother is guilting me into babysitting him. “Why can’t you just put him in a group home?” I plead.

I acquiesce though, as I always do with my mother, and it is decided that we will meet at a fast food restaurant halfway between our two homes for the exchange.

I’ll have to hide the man from the egg.

—

I had been just as surprised as one might expect when, at the age of ten, while making breakfast one morning, I cracked open what I thought was a normal chicken egg and found, covered in egg white, a tiny naked man—full head of hair, a Roman nose, strong tightly-muscled arms. So statuesque, lying prone in my mixing bowl. I didn’t want to touch him at first—I was so astonished to find a man in an egg.

I slowly reached my hand into the bowl, and as delicately as possible rolled my fingers underneath his body and lifted him. Light, like a baby bird. His body limp as a child who has fallen asleep and must be carried to bed. I considered for a second running him under the tap to rinse him off, but I didn’t want to injure him, so I poured some warm water into a cereal bowl and placed him in the bowl as if he were taking a bath. With cotton balls and Q-tips, I bathed him. I became embarrassed looking at his naked form lying in the makeshift tub of warm water and egg white, so I lifted him out and placed him on a towel where I gently dried him off. I retrieved a napkin from a drawer and lay it on him like a blanket.

Breathing. He was breathing. Breathing meant life. Breath is life, so I eyed the man’s chest as if watching a loved one in a hospital bed. At first I swore I was imagining it, a hallucination caused by staring so long, but the napkin was moving. I marveled at how his tiny chest expanded and contracted. The man was breathing. He was alive. I thought, no one can know. I had to go to school, and I didn’t want to leave the man in bed, so I hid him high in my closet.

—

Cliff is sure to snoop, and I can’t just hide the man away in a drawer or a cupboard. He certainly can’t be sitting out. I can already hear Cliff needling me. I have managed the keep the man hidden from Cliff all of our lives. I put the man and his bed inside a box and place the box high up on a closet shelf, just as I had done as a child.

Cliff’s invasion is just as uncomfortable and miserable as I expected it would be.

On the ride to my house, he asks, “You jerk off in this car? Smells like you jerk off in here.”

I have learned to remain silent. Eventually, Cliff will tire of antagonizing me. But he doesn’t.

“What do you do again? Set up Internet porn sites? Kiddie porn, right?”

I don’t respond. I can see him pinching the scar tissue on his jawline like it’s a Halloween mask that doesn’t fit right.

“Mom thinks you’re gay. I told her you’re a virgin.”

I stay quiet. He clicks his dentures.

“Maria says you’re cute, but your nose is a little too Heeby.”

“I bought you crazy straws because Mother says you like crazy straws,” I tell him. “You still have to use straws, right?” That shuts him up.

When we arrive at my house, I show him to the guest room and ask him to please smoke outside.

“I’ll open the window,” he says and shuts the door.

At night, I pull down the box and check on the man.

With my bedroom door locked, I set the man on my pillow. He sits so still, yet with such vibrancy that I would not be surprised if he finally speaks back to me. He listens to my complaints about Cliff. Mother has always regarded Cliff like a toy or a pet, although I don’t know who controls whom. I speak to the man more than I have in years, my face dwarfing his body as I whisper my grievances to him.

I tell him about how Cliff looks so much older this time than he had the last time I saw him, how his breath reeks of oxidized metal, how he always asks me when I am going to meet a girl or if I am a faggot.

—

With Mother and Cliff at the hospital, I created a small throne out of some books, and I set the man in the chair on my desk. He wasn’t limp, but he wasn’t stiff either; more like someone asleep, rigid yet pliable. With the napkin tied about him, he looked like Caesar. With my finger, I parted his hair. I sat on my bed and watched him, his eyes were closed as if in meditation.

The phone rang. I didn’t want to answer it, but if it were Mother, she would be upset. It was Mother. Cliff was awake. She would be sleeping at the hospital tonight. I was to take a bus to the hospital after school. I left the phone off its cradle and returned to my room.

They opened. His eyes. They opened, and he was looking straight ahead. I had seen those dolls, the ones whose eyes open when you sit them up. Their eyelids are up, but their stares are vacant. There was depth to his eyes. He was seeing me, comprehending me.

I didn’t know what else to do, so I began talking to the man—questions at first: Who are you? Where do you come from? Questions with no answers.

His face was so kind and gentle that I began to tell the man from the egg about my life—about my father who lived somewhere else, my mother who was always yelling and apologizing, bullies, my love for reading. I told him about my fear of being alone and my need for solitude. I told him about Cliff who had been mauled by a dog; how he was still in the hospital, which was why I was home alone making breakfast. “That’s how I found you,” I said.

The man remained silent, his only movement the expansion of his chest and the blinking of his eyes. With time, I thought, maybe he will speak.

—

My eyes are burning. It’s three a.m., and I have been talking all night to the man from the egg. He looks asleep, and I begin to sing to him, a German lullaby that my mother had sung to Cliff in the hospital: “Schlaf, Kindlein schlaf. Schlaf, Kindlein schlaf. Der Vater hüt die Schaf, die Mutter schüttelt’s Bäumelein, da fällt herab ein Träumelein. Schlaf, Kindlein schlaf.”

I sing of the father taking care of the sheep while the mother shakes dreams from a tree, and I look down at him, my little man who came from an egg so many years ago. Sleep, child, sleep. I haven’t sung that song to the man for a long time. I turn off the lights, and I go to sleep. I dream of the hospital.

—

After he came out of his coma, Cliff stayed in intensive care for months. After school, our neighbor would drive me up there. My mother had worked nearby, so she would be there when I arrived, leaning over Cliff in his bed, dabbing a wet washcloth on his face. She’d brush his hair and swab inside his ears and sing him her German lullaby. She had called him her little doll, and my stomach tightened every time she said it.

She had never said anything when I walked in, just kept talking to Cliff. He would be asleep, but she would tell him all about her day at work, how her drawer had come up one dollar short, and the manager treated it like it was a federal offense.

I spent that summer playing alone during the day and sitting in silence in a hospital room at night. She could have asked if I could stay with neighbors, but I think she wanted me to see what I had done to Cliff. And I saw.

When I would come home, the man from the egg would be sitting where I’d left him. On my dresser, I arranged his bed, and I laid the man down. I read to him from Gulliver’s Travels until I fell asleep. And so we lived.

—

I come home from work to find the man’s box house sitting on the kitchen table. He is not inside. Watching me frantically searching, Cliff asks, “Looking for your toy?”

“Where is the man?” I ask.

He asks what man.

“The man,” I snap.

“I threw it out. Adult men do not play with dolls. And they think I’m fucked up.”

It isn’t a fucking doll, I want to shout, but shouting at Cliff only encourages him. I know he hasn’t thrown the man out, so I sit at the table and wait. I just have to be patient. Cliff sits down opposite me and whistles; because of the scar, his upper lip always snarls. The sound is reedy and broken.

He pulls the man out from between his legs and chucks him on the table, naked.

“It’s pretty lifelike,” says Cliff. “Needs a dick though. A teenie wienie.”

“What did you—” I begin, but Cliff cuts me off.

“You’re into some pretty kinky shit,” he says.

And then I do the worst thing I possibly can: I cry; something I haven’t done since I left home. Cliff laughs, and when he opens his mouth, his partial denture comes loose. He removes it, and half of his face collapses. I can’t look at him.

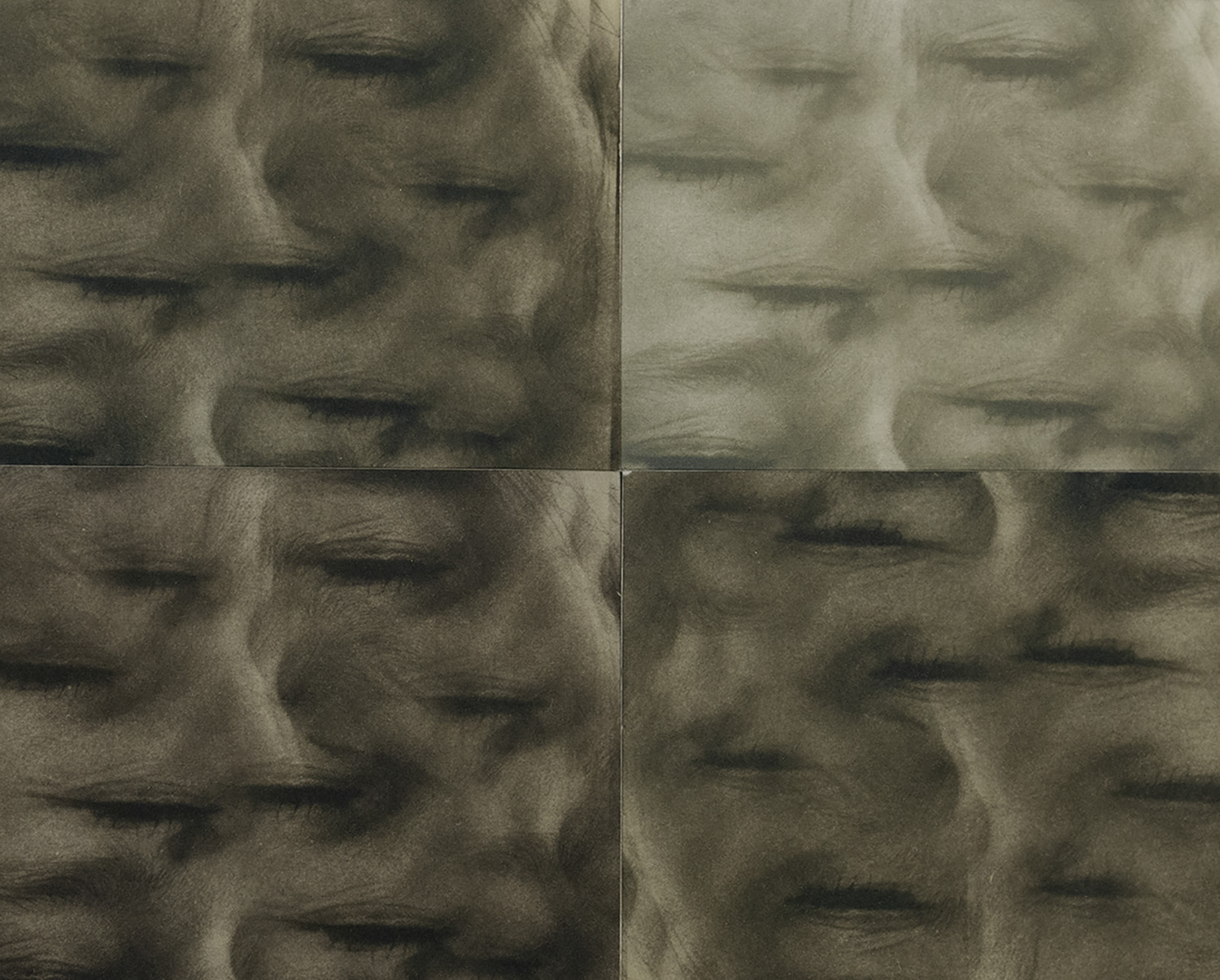

I pick up the man, go into the bathroom and close the door. I unroll some toilet paper and lay him on it on the counter. Looking at him, I see for the first time since I picked him up that he looks like a child’s ruined toy. His hair is gone except for a couple of patches behind his ears. His face is sunken and crooked. His eyes are closed. Cliff has attacked him with a sharpie. Crudely drawn swastikas are emblazoned on his chest. His stomach is marked with two lightning-bolt S’s. His frail forearms also bear the same lightning bolts as on Cliff’s arms.

He looks like a monster.

—

When Cliff came home from the hospital, and for years after, strangers would call him a monster. Mothers would warn them to keep close and not to stare. My own mother forced me to look after Cliff, walking him to school, eating lunch with him, and later, when I could drive, taking him with me to the mall or the movies.

He didn’t just look like a horror movie; his behavior was horrific. I’d be walking behind him and he’d just start singing or high-fiving people. Those who weren’t disgusted would laugh and call him “Cliffy”; he didn’t know they were laughing at him.

They elected him class president as a joke, and he got cast as the Phantom of the Opera even though he couldn’t sing. When I told him people were just playing a joke on him, he got mad and lashed out at me: hitting me, putting bugs in my bed, and spitting in my cereal. Every night before bed, even though I had never been to church a day in my life, I sat with the man from the egg and prayed. I prayed for Cliff’s death.

Cliff did not die. He was always sick though, and eventually, despite his pleas, Mother withdrew him from school. He became her project. She taught him Bridge and calligraphy. She bought him a computer and an AOL account so he could meet people.

I remember coming home from school right before I graduated and went to college. They were sitting at the kitchen table. Cliff was smiling. For the first time since he was attacked, he had a full set of teeth.

“Just look at my little doll,” Mother had said. “Doesn’t he just look handsome?”

Any compassion and love she had had for Cliff was withheld from me. If I had left one shirt out of the hamper, Mother held me in contempt, while Cliff’s room smelled sour, littered with filth. If I complained, she rushed to his defense with some excuse about his condition. I was the lucky one, she’d say. What if I had been attacked by that dog?

—

“I always had you,” I tell the man from the egg. But I can tell, looking at him marred and mangled, that he too is gone.

When I feel like I have stopped crying and am brave enough to face him, I come out. Cliff sits looking like a comic book villain.

“You’ve maimed him,” I say, tightening my face to hold back tears.

“Did you see his back?” asks Cliff.

I roll the man over in my hand and see that awful name written in some attempt at a gothic script. Above it, “Heil” is misspelled. On his right bare buttock, the word actually beginning nearly inside of him, Cliff has scrawled “Jews.”

I say aloud what I have muttered under my breath to god hundreds of times: “I wish you were dead.”

His phlegmy, distorted laugh comes immediately. “You think I don’t know that? You fucking retard.” Then he walks right up to me, past the man from the egg lying broken on the table. Cliff picks him up, holds him by his foot, and drops him on the table like a cat dropping a dead mouse. He puts his face next to mine and says, “I hope you live forever.”

Then he leaves.

I retrieve the bowl that has been the man’s bathtub for twenty years and set him to soak in warm, soapy water, hoping that the marker will fade.

As he soaks, I tell him again what happened the day I left.

—

“Remember,” I say. “Cliff was sixteen.” I had been accepted at a summer program on campus, a sort of camp for computer programming. All that school year, Cliff and I had sat alone in separate bedrooms, staring at computer screens. Two alien brothers sitting in the dark, finding solace in the lights from our monitors. Of course, I had the man from the egg to keep me company.

I had packed my car the night before, the plan being that I would get up and leave. When I had gone out to the driveway, I saw that one of my tires was flat. On closer inspection, I found that it had been slashed. Even though we hadn’t spoken more than a few words to each other in months, I knew Cliff was the culprit.

Without telling my mother or confronting my brother, I replaced the tire with a spare and left.

—

The ink becomes lighter but does not wash off. I lay the man naked on his bed, and I cover him again with a napkin. I try to sleep, but I keep checking on the man.

—

Throughout college and into adulthood, my tiny, silent roommate remained. Every couple of days I would remove the doll clothing I had bought for him and wash it, bathe him with a cotton ball, and brush his hair.

Through exams and deadlines and interviews, my diminutive friend was with me. When I got my first real job, I would tell him about my day at work, the tedium of reading lines of code, my abrasive cubicle mate who smelled of women’s perfume, the fire alarm that forced me to interact with others as we stood in the parking lot. He remained mute. I never named him, always hoping he would speak and reveal his name to me.

Besides the man, my only connections with others were the anonymous friends I had made playing games online. My avatar was friend or enemy to their avatars, and beyond the threat that “we should get together one day,” we never truly met.

—

Cliff comes back some time in the middle of the night, drunk and loud and calling out, “Jamie,” the name I grew up with but hadn’t used since I went away to college.

I cover the man completely and go out to face my brother. In the dim light from the streetlamp outside my kitchen window, I can see that Cliff’s face is bleeding. I turn on a lamp, not wanting to see him in the full glare of the overhead lights. One of his eyes is swollen shut.

“What happened?” I ask, genuinely concerned, and surprised at myself for being so.

“Bit by a dog,” he says.

“What?” I say, hoping I heard him wrong.

“Some guy didn’t want me talking to his girlfriend.”

“So he hit you?” His initial answer is still folding itself into my mind.

“There were words exchanged. I think Jew Bastard was the one that did the trick.”

I get Cliff a bag of frozen strawberries and sit at the table with him. With his black eye and busted lip, he looks much more like a human being. I sit with him in my kitchen, watching him nod in and out of consciousness.

“About your thing, your doll, I’m—”

“I just wanted to scare you,” I say.

“With the doll?” Cliff is more awake now.

“No. The dog. I just wanted to scare you. You were so cocky and self-assured. Everybody thought you were older than me. I dared you to pet the dog.” I had dared him to pet the dog, and he did. And the dog hadn’t done anything. That dog had barked at me every day like it wanted to rip my head off, and it let Cliff pet it. So I had thrown a stick.

Cliff is clicking his dentures.

“I ran to you when the dog knocked you over, but it snapped at me, so I ran back to the tree.”

I have relived that moment every single day of my life. I’d be stopped at a red light and see a dog in the car next to me and then my brother having his face bitten off. I’d hear a siren and see all of those emergency vehicles blocking the street. I can still feel the bark on my fingertips, smell the grass, taste the bile rising in my throat. Cliff had been silent as they gently rolled their hands under his body and lifted him onto the stretcher. I thought he had died.

Cliff chuckles. Maybe he is too drunk and doesn’t understand me.

“Are you dying?”

“What?” I ask.

“Do you have AIDS or something?”

“Why would—”

“Ass cancer? Your touching death-bed confession and all.”

“I’m apologizing.”

“Why?”

“It was my fault,” I yell like I am accusing him of stealing my guilt.

“You’re thirty years old,” he says. “Are you really still thinking about that shit?” He looks at me with his one good eye and shakes his head.

We sit in silence, Cliff nodding in and out of consciousness.

After Cliff passes out at the table, I fold a towel under his head. I don’t even look at the man from the egg as I get into bed.

Cliff’s departure is a silent one. As I drive him to meet my mother, I hold an imagined conversation with him in which I tell him I am ashamed. I want to tell him I am happy he has found love, that he deserves it. He wordlessly says he forgives me. I could never imagine him telling me he loves me.

When we pull into the parking lot of the fast food place, Cliff gets out of the car without saying thank you or goodbye. He then turns back to the car, knocks on the window, and says, “Pop the trunk so I can get my shit, bro.” It’s the first time he’s called me that.

I return home to the man from the egg. When I pull back the napkin, I’m not as shocked as I thought I’d be. He doesn’t look human anymore, and I don’t feel the need to trim the stray hairs Cliff has left or put him back in his clothes.

I do sit with him though, there at the table where I told my brother the truth. A truth that only mattered to me.

I wrap the man in a napkin, lay him gently in a box, and close the flaps.

—

The hospital gift shop smelled like a pharmacy. Every day I flipped through word searches and coloring books. I read the get-well cards. None of them were fit for Cliff. I smelled the flowers, although they all smelled like disinfectant. In the small toy section, there were stuffed lions and dogs; a baby doll whose eyes opened when she was upright and closed when she was lying down; plastic trucks and cars. On the floor behind a bin, I saw a pair of bare feet. A man–smaller than a Barbie but bigger than my action figures. He was naked. I sat against the wall, my own feet sticking out into the aisle. He had hair like paintbrush bristles. I smoothed it down on his head with my thumb.

The old lady who blew up balloons told me I needed to scoot. She asked me, “Is that yours?”

“Yes,” I said.

“You need to get him some clothes. He’ll freeze to death.”

“Okay,” I said, holding the man close to my chest as I walked up to Cliff’s room.

“Mother,” I said as I walked in. “I found—“

“Be quiet,” she said. “He’s sleeping.” She turned back to Cliff, his face like a crumpled up wad of bandages. “Schlaf, Kindlein schlaf.”

I backed out of the room and went down to the hospital lobby to wait for my ride home.

Michael Mau’s short fiction has appeared in Black Warrior Review, Portland Review, Fifth Wednesday, and other places. “An Open Letter to America From a Public School Teacher,” originally published in McSweeney’s, received national attention when it was picked up by several news outlets. His story “Little Bird” was selected by Lily Hoang as the winner of the Black Warrior Review Fiction Contest. His story “Best Launderette” was selected by guest editor Pam Houston for Fifth Wednesday Journal. Michael was a finalist for the 2017 Disquiet Prize. Find him at www.michaelmau.org or on Insta @michael_mau_.