Nonfiction by Renée Branum

Grandma Wanda used the word “hysterical” to describe anything worthy of extreme laughter. Her laugh began as a low burst, like an exploding balloon, and then receded toward a series of open-throated guttural “gar gar gars.”

She had a deep, back-of-the-mouth cackle. She was one of those who would, quite literally, throw back her head, directing the laugh upward so it seemed to seep like a slightly clogged fountain.

Afterward, when things began to settle, we’d watch her wipe at the corners of her eyes, saying “Well, that’s just hysterical.” It was sort of an apology, for being momentarily absent from us, lost in her tunnels of hysteria. Her reddish hair moved as her head bobbed along its own currents, her strands of copper lightning gone electric.

She laughed at all forms of body humor. She loved stories of ill-timed farts. She laughed when affectionately teased. She laughed when, as children, my sister and I took ourselves too seriously. She laughed at The Andy Griffith Show, at my impression of a drunk pirate, at a certain photograph of my father as a baby sitting in a metal bucket, impossibly fat.

Wanda was prone to fits of hysterics, was known to fall out of her chair laughing on occasion. She would quiver on the carpet, folded up like a hand that couldn’t quite make a fist. And because she was old, was always old as far as I can remember, this was a little frightening. It forced us to think of seizures, of the heart quickening and then going slack. It was frightening for other reasons too, even though we always laughed with her. We bore witness to her nearing some shimmery edge, a vague line we weren’t sure she’d come back from. She dipped toward a loss of self. We worried she might disappear.

She always came back to us though. The smoke of her laughter cleared while her hands forced her hair to settle back into itself. “I don’t know what got into me,” she’d say.

Wanda hated having her picture taken, but hated most being photographed in this state – shaking and wild, loosened. Once, passing around pictures from a recent vacation, she caught sight of herself laughing and crazy-haired atop an open-air tour bus. She grabbed the photograph, tore it across, ripping it into smaller and smaller scraps until it became a handful of glossy confetti.

Hysteria is an old word. For a long, long time people have sought a word for this state. In Greek, it speaks of the womb, belonging to the womb, suffering in the womb. Plato described the uterus as an animal, roaming between the borders of flesh, shifting as a woman moved or kept still, restless and straining. It did not sleep while the world slept.

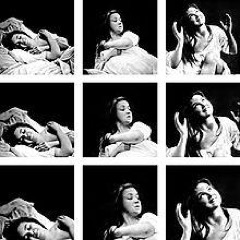

In 1878, Jean-Martin Charcot published a series of photographs documenting women in various states of hysteria. He believed that hysteria was a product of the mind rather than the womb. He experimented with the idea of “animal magnetism,” a kind of hypnotic healing. To Charcot, it made sense that each animal should exert an invisible energy that could be manipulated. He laid his hands on the patients, pressing against the soft place at the base of the neck and they went into fits, sprawling against the sheets, arms spread crosswise and open, as if ready to receive.

Nearby, a photographer dipped his head beneath a black cloth, loaded a glass plate into his camera, and opened the shutter.

Wanda once told me that at Yosemite National Park, rangers used to drop burning logs from the top of a cliff at nightfall, a long trailing spill of hot embers falling 3,000 feet. From the valley floor below, it looked like a flaming waterfall.

“It was hard to look at, it was so beautiful,” she told me.

In 1968, the tradition ended. The last Firefall took place that summer, and Wanda stood thin-lipped and squinting beside my father and grandfather, watching the embers loosen in the air, a tangle of flame like her hair in the midst of laughter, a silent tumble as they sparked and stuttered down toward the meadow.

Turning away, she said to her son and husband, “Well, I guess that’s that.”

On the phone, my mother tells me about the baby, a boy, who died at birth before my father was born and how Wanda was “never quite the same after that;” how, according to my father, she would gut rooms suddenly, leave things stacked in piles for weeks on end while she stripped the paint from the walls, covered them again with a new color, and then gradually, like a receding storm, the paint would dry, the pictures would find their old places on the walls, now freshly blue. It would happen without warning. It scared my father in its suddenness, its fury.

Once, the sound of scraping paint coming from down the hall, my grandfather pulled my dad aside, tried to use words about birth and dying as gently as he could, and told him he’d almost had a brother but that he must never, ever, under any circumstances, mention it to his mother. And that was that. Wanda wanted to be alone with this. We never spoke of it.

But there were were still moments when a dark presence entered the room. My grandmother writhing on the floor, crippled with laughter and clutching her stomach, a joy twin to suffering. We saw his reach. We saw it, and we laughed with her.

I remember my father standing in the center of our living room, turning around in a slow circle and saying, “This room was meant for Christmas.”

After Wanda died, I suddenly realized how small our family was, how the circle we made when seated in that living room had shrunk. It now became easy to imagine what my father’s Christmases were like when he was a child – the warm room, the lit tree, my grandparents watching a little boy wearing thick glasses while he knelt on the floor, tore bright paper to see what was underneath. His parents watched him as he lifted each thing from the tissue paper, turned it over in his hands, nearly hysterical with joy.

For the first time, I think: It must’ve been lonely. My father, alone in his excitement. My grandmother, alone in her persistent grief. My grandfather, alone in his quiet, in his efforts to navigate his wife’s sorrow, his son’s joy, to stand between them and try to offer some sort of reconciliation.

That was how it was. That was how the three of them lived.

The Charcot images seem so obviously staged. It is strange to think of him lifting away a sweaty coil of his patient’s hair so her face could be visible to the camera, of directing her to cross her arms neatly across her chest – a tidy image of hysteria.

His most famous patient was Marie “Blanche” Wittmann, an epileptic at the Salpêtrière Hospital who became known as the “Queen of Hysterics.” On a weekly basis, Charcot would perform hypnosis on her, and she would go into hysterical fits for an audience of curious academics, scientists, and psychologists. Sigmund Freud was among those who bore witness to her hysterics.

Upon Charcot’s death in 1893, the “Queen of Hysterics” was apparently cured of her fits. She never suffered from convulsions again.

I have seen my grandmother cry with her whole face – the wrinkles holding water like bright canals.

After my grandfather’s funeral, as they carried the coffin through the doors that led to the little gravel lot behind the funeral home, Wanda waved very sweetly, as if he were going on a voyage, and said, “Bye-bye, Donnie.” Then she smacked her palm down on the coffin’s lid as it disappeared through the door, and started to sob. Her mouth opened and her bottom lip seemed to retreat, like when she’d remove her dentures at night. When I was a child, I liked to watch her hold her teeth in her hand while she brushed them, loved the pinkness of her mouth opening when she looked at herself in the mirror and laughed at the coral-colored emptiness there.

At the funeral, when she sobbed, it sounded a little like her laughter, that same “gar gar gar” when, as children, my sister and I staged a production of A Christmas Carol and, delighted by how miniscule and serious I was in the role of Marley’s ghost, Wanda had thrown back her head and gargled out a thunderous laugh when I’d wailed, “Tis a ponderous chain!” while rattling my tinfoil shackles.

When she touched the coffin, I cried too. I was ten-years-old and it was my first real grief – a grief that was not for my grandfather or the loss of him, but for her. Though I was so young, I knew it was unlikely I would ever witness a more private moment than my grandmother saying, “Bye-bye, Donnie.”. They were married fifty-four years.

This, I think, is hysteria: a moment in which something from the private, the intimate sphere, comes upon you suddenly and flashes outward into the realm of the observable, into a public space. It is being overtaken by, even powerless to, the force of your own spirit. Baudelaire famously said, “I have cultivated my hysteria with pleasure and terror.”

Charcot believed that the use of hypnosis could force the private sphere into the public eye. It has since been written in a study of Charcot that “Charcot and his school considered the ability to be hypnotized as a clinical feature of hysteria … For the members of the Salpêtrière School, susceptibility to hypnotism was synonymous with disease.”

And when I think of hypnosis, I think of my grandmother’s face when she described the Yosemite Firefall – how it seemed spread across with a soft reverence for this unreachable thing, caught between the separate pulls of grief and laughter.

The ritual, she told us, went like this: a master of ceremonies stood on the valley floor where the crowd gathered. A “fire handler” stood up on the cliff top where he kept a bonfire going. When darkness had finally thickened and blued, one man would call up to the other, “Is the fire ready?” and the tiny murmur of a far-off shout would trickle down, “The fire is ready!” And then there’d be a moment of waiting, darkness getting darker by mere inches, shades, and then they’d hear a call coming through cupped hands: “Let the fire fall!” followed by the briefest pause, a heartbeat, tripping over that last extended moment of anticipation, before the final call, simultaneous almost with the act itself, a description of it in the most present of tenses: “The fire is falling!”

And then the embers would already be in the air, loosening through their fall, a silent tumble sparking and scattering down toward the meadow. The plunge seemed nearly weightless to the observer, the glow both blurred and sharp, like a line of lava with hard edges. Every part of the fire kept itself distinct as it gripped the air, the whole sight a little too intimate, as if everyone gathered there were watching a woman through a lit window, seeing her raise her arms at the end of the day, to release the clasp of a necklace, or untie a ribbon and let down a heavy coil of auburn hair.

Renée Branum recently graduated with an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of Montana. She received an MFA in Fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2013 where she was a Truman Capote Fellow and a recipient of the Prairie Lights Jack Leggett Fiction Prize. Renée’s fiction has appeared in Blackbird,The Long Story, The Georgia Review, and Narrative Magazine with stories forthcoming in Tampa Review and Alaska Quarterly Review. Her nonfiction essays have been published in Fields Magazine, Texas Review, True Story, Chicago Quarterly Review, Denver Quarterly, Hobart, and The Gettysburg Review. Her essay “Certainty” was awarded first prize in The Los Angeles Review’s Fall 2016 Nonfiction Contest. Her essay “Bolt” received first place recognition in The Florida Review’s 2017 Editors’ Awards. She received two Pushcart nominations for work published in 2017. She currently lives and writes in Tempe, Arizona, where she works as an academic tutor.