Nonfiction by Sean Prentiss

Kingfisher

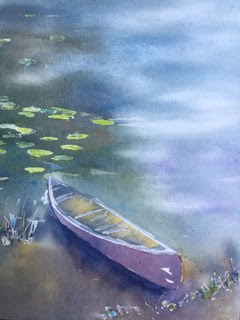

Sarah’s birthday morning, she and her father in one canoe, casting into a stillwater lake. Blue dog and I in another, the solo canoe. Blue whining for land, whining to chase after frogs and snakes.

I clumsily cast a spinner toward shore. Sarah and her father cast beside the fallen birch tree

We throw. The bobber splashes. We reel in. We catch nothing more than two logs and one sunny, off Sarah’s father’s hook.

Nearby, we hear the clamorous, mechanical, machine-gun cackle of a mohawked kingfisher stalling inches above water, an all-seeing god seering out fish that hope the water’s sheen offers safety.

It doesn’t.

This ash bird—slight enough to light upon my palm, beak long and stout, rounded body tapered toward tiny feet—resembles campfire smoke upon wings aflutter.

Until it shatters water.

The kingfisher flies from water with a fish perpendicular in its soot-gray beak.

After feeding, perched upon a birch, the kingfisher offers a piercing rattle of avian skewery soon, once more, to come, while Sarah, her father, and I futilely cast, hoping to catch what we cannot see, hoping to reel in what we cannot find.

Wood Duck Triptych

- Return of the Wilderness Rainbow

Once Solstice Lake April’s last ice slivers open and lake water re-emerges after longest winter. No more than a day later, they arrive, a pair, mated since fall.

The hen, drab and ready to secret herself away during nesting in some tree cavity.

The drake, a wilderness rainbow—bejeweled plumage, iridescent green crown, a neck of winter snow, inferno eyes, and a brown chest speckled with a Milky Way of white stars.

2. Never as Pretty as Plumage

A century ago, these Solstice Lake wetlands and most of the other Vermont marshes were backfilled in by our ancestors, longing to invent land into existence.

Bogs and marshes became farms and home lots.

Wood ducks were hunted beside beavers until each were mostly vanished, hunted for meat and eggs and plumage to make us pretty, though never as pretty as those lake princes.

Finally, our ancestors paused their slaughter—(Do we ever cease destroying?)—a moratorium on wood duck hunting from 1918 till 1943. Beavers, also, allowed to return to whirling fields and streams into marshes—like this marsh paused on the edge of Turtle Cove.

Lakes glistening again with the reflection of the resurrected wood duck.

3. A Great Faith

Now returned to her nesting waters, the hen searches for a hollowed tree left vacant by a pileated woodpecker. Safety here, twenty feet above the marsh and the prying teeth of raccoons.

Secreted away like a dream held tightly within our minds, this mother lays ten eggs, incubating them thirty days.

The day they hatch, the precocial ducklings are called—kuk kuk kuk—from their perched nest by hen waiting in the marsh below.

These chicks—some great faith swelling inside them—leap though they know not how to fly, fledging themselves from nest. They air-tumble-and-spin, plummeting, till they bounce off moss of marsh.

Once land gathered, mother walks this paddle of ducks into marsh-water to turn a life born in sky into jewels upon water.

Great Blue Heron

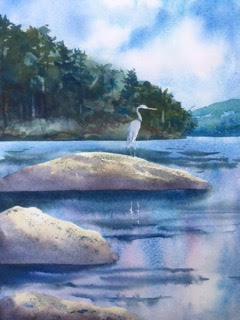

- At Rest

Stock-still where marsh grass seeps into green water.

Stilt-leg half draped in water, other hooked forward, a slow motion stalk around the suspicion of frogs and fish.

A measured step.

A pause swelling until it seems this creature of flight—all matte gray feathers, a reedy, white neck, thin slip of blue feathers, slight crown, and rusty thighs—is a statue frozen, its wings now nothing more than decor, toes transformed into roots gripping the muck of earth.

2. At Hunt

The flash of yellow bayonet, splash of water, neck’s violent recoil, a bridal veil of water.

A catfish, gut-impaled like a flag run up a pole, flops and flinches. The hen works the fish off its spear-beak into its gaping yawn. The fish dives—as if swimming from some danger above—down the long river that is the heron’s throat-canal.

3. Great Blue Heron, Hunting

For Sarah Eve, for Winter Eve

Knee deep in evening, this heron casts and re-casts a razored beak, aiming for what shimmers beneath the Solstice Lake sheen.

All day this hen harvests fish and frogs, lingering into evening, the sun fading into Solstice Mountain. Still, she refuses to fly from cove’s edge, maybe because of what waits at her heronry, a ruckus of chicks, ravenous and soon-to-be rowdy.

4. At Flight

For Sarah Eve, for Winter Eve

A wisp of evening fog curled upon cove. The air reeking of muck and marsh. A hen in flight, the s-curve of neck cradled into its dawn-gray body, reedy legs echoing behind like an almost forgotten idea or barely heard song.

Widespread wings rippling long, soft sweeps that stroke circles upon tranquil Solstice Lake.

How do I learn to kiss what I love as gently as a heron’s wings?

Biography of a Lake

Beneath the sheen, beneath the reflections and the ripples, Solstice Lake is a bustling aquatic community: smallmouth bass, brown bullhead, yellow perch, chain pickerel, pumpkinseed, golden shiner, white sucker, and in the deepest, coldest parts, brown trout, a thousand trucked and dumped in each summer. The others all native. Fish bred and born here in this Vermont lake.

I lean into loving those natives, those fish that can trace their lineage back to these rivers, brooks, and kettle pond lakes, to time immemorial here in Vermont’s water. But then Richard pulls up a brown trout—a European fish brought to Vermont in the 1800s—from the depths of Trillium Cove.

This fish is streaked yellow from pectoral to caudal fins in a way that makes it seem as if the sun has cast a dawn glow upon its belly. Red orbs are burned into this trout’s side, an orbit of many small Mars’s. A shotgun blast of black upon upper ridges.

Held in Sarah’s father’s hands is this outsider fish. After nearly two hundred years in Vermont, it is now considered naturalized to these water. Not invasive. Never native. This brown trout can never claim it came from here, can never claim these waters as its truest home. Still, this brown trout has learned to live in companionship with native perch and pickerel, those bullheads and bass.

Each year, brown trout are loosened into our waters, submerged into new aquatic homes. Held in a hand, it is easier to dream myself not into those natives but into a brown trout swimming new within the depths of Solstice Lake.

I, too, am not from here.

I am a Pennsylvanian by birth. A Westerner by education and exploration. Even from a line that can be traced back to another continent, another European world.

But now, like that brown trout re-released into the water, I am naturalized to the isolation of Solstice Lake. Coming later, coming home.

Sean Prentiss is the award-winning author of Finding Abbey: a Search for Edward Abbey and His Hidden Desert Grave, a memoir about Edward Abbey and the search for home. Finding Abbey won the 2015 National Outdoor Book Award for History/Biography, the Utah Book Award for Nonfiction, and the New Mexico-Arizona Book Award for Biography. It was also a Vermont Book Award and Colorado Book Award finalist. Prentiss is the co-author of the environmental writing textbook, Environmental and Nature Writing: A Craft Guide and Anthology, and the co-editor of The Far Edges of the Fourth Genre: Explorations in Creative Nonfiction, a creative nonfiction craft anthology. Prentiss is also the series editor of the Bloomsbury Publishing Writers Guide Series. This textbook line includes a variety of forthcoming textbooks all focused around creative writing. He and his family live on a small lake in northern Vermont and he teaches at Norwich University and in the M.F.A. program at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Richard Henry Hingston is a painter and retired art teacher who taught for nearly four decades . He has spent many seasons on mountain lakes throughout the northeast , drawing on their inspiration as an ally in his visual expression , and , enjoying the elements of rhythm , harmony, and fluidity that watercolor and nature share . He lives with his wife Marjorie in Delaware. rhh1742@gmail.com