By Sophie Weiner

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of Tsim Tsum (Saturnalia, 2009), The Babies (Saturnalia, 2004), and the chapbook Walter B.’s Extraordinary Cousin Arrives for a Visit & Other Tales (Woodland Editions, 2006).

She received a BA from Barnard College, Columbia, an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and a PhD from the University of Georgia.

The prose poems of The Babies and Tsim Tsum are a rare event, and it’s still happening. On the back cover of Tsim Tsum Stephen Burt says of Mark’s book, “You’ll remember what Mark has done with the prose poem: you’ll wonder how on Earth she does it, too.”

I contacted Mark this past summer in something of a fever, after encountering on her website the phrase, “live plants, corsages.” Is it possible, I wondered, to make grow again, something cut off from its life source?

You will follow her to the place called Mother, and to the cloud that cracks open to spill out men like many yolks.

And she’s come for your trash.

The following interview was conducted over email.

First, thank you very much for speaking with me. I’m a very big fan of your work.

In your Eleventh Hour lecture, “The Poet as Collector,” you start by describing a project you’d been working on. You said:

Over the past few weeks I have gone from poet to poet asking for their trash, their rust, their fading lines, lines on the verge of decomposition. I am working on an essay that will reveal this teetering heap. This tower of compost. How do we differentiate the junk from the treasure? What grows out of our collective debris? A humming? A hymn? A nothing? I’ve been told if you stare into the dumpster long enough eventually eyes, or something like eyes, begin to stare back.

What about the “collective debris” of poets, or the line on the verge of decay is most interesting to you? How did this project begin?

I think the project began as most projects begin: with that thing called “Hope” laced with fever and blindness. I had this idea that through this act of rescue, I could make a kind of prayer poem. I imagined what poets shed could be sewn into a skin the world could wear when the world got too cold (or too hot, for that matter). “Dear Poet,” I wrote. “I have come for your trash.”

I wrote, “I am working on an essay on debris. Specifically, lines poets throw away. My goal is to build a glowing city out of garbage. I am thinking about the history of ruin and repair. I am thinking about rescue. Sometimes I imagine it as holding the body against my body so it never turns into a ghost. There will be some mysticism here. And there will be some foul play. Will you send me a line? Even if it’s a word or two? You will, of course, be carefully cited.”

Some promised me their lines and never sent. Some couldn’t stop sending. Many ignored me. Ariana Reines sent me a photo of a dumpster named LIBERTY which solved the whole riddle before I even began writing, but I carried on. One poet told me he’s keeping his trash thank you very much. A few sent me edits, asking me to tweak their dreck. Some regretted saying yes. Josh Bell wrote, “It’s about time!” It was sometimes funny, but mostly it felt shameful. It occurred to me I might be begging for garbage. The lines piled up one on top of each other like a big mistake. I looked at them out of the corner of my eye. They couldn’t really care less about me.

Many of the lines referred, it seemed to the body and what had not happened and what was missed, and many of the lines referred it seemed to not knowing and failure, an inability to decipher, a question not asked, and things off in the distance.

It strikes me too that the project of collecting other poet’s trash seems linked to a theme common to your books: exile. I’m thinking also of a phrase I found on your website, “live plants, corsages—” the idea that something that has been cut off, so to speak, or removed from that which keeps it alive, turned into a kind of product of ornament but one that withers, can still sustain life— I love this idea. Is there a relationship between the two for you? Is there a way in which a “tower of compost” is at all like a kind of exile? And what grows there? And how?

This question is so beautiful I wish I could wear it around my wrist like a dying flower.

Years ago, when I lived in New York City, there was a store in the East Village called Obscura that I would often visit. It still exists but now it lives at a different location: http://www.obscuraantiques.com/ It had, I remember, a dark green awning, and on the side of the awning it had once read Live Plants Corsages. Which is to say, Live Plants Corsages had been painted over or scrubbed off, but it was still very much legible like a body under a thin sheet. The store was filled with taxidermy, and old dentist trays pocked with teeth, and broken dolls, and bone dice, and medicine bottles, and antique safety pins, and Russian flight goggles, and lace gloves too small to ever fit anyone I’ve ever known. Everything in the store was in a state of exile, as each thing was removed from what once kept it. But there everything still was. Safe and sound, and odd, and bewildered.

In retrospect, I must’ve gone there as often as I did because it gave me comfort. I felt a sense of belonging. “Live Plants Corsages” became a tiny prayer I would say to myself because it summoned up for me this idea of a home where everything was in exile, but in exile was where everything belonged.

You said in your lecture that there is a lot of shame in the process, asking people for their trash—have you found that to continue to be true, is it a bad idea?

Halfway through this project, my son broke his arm and then soon after the doctors found a dark spot inside my husband. A poet friend wrote, “it occurred to me this morning that maybe when you asked the universe (poets) for their trash you got some stuff that maybe wasn’t the most useful right now… i do NOT NOT NOT mean to imply that you are at fault for ANY of this in any way, but I wonder if saying a prayer or making a request for the poets/ universe to take some of your worries AWAY or to send you healing and blessings… i don’t know — just thinking…”

And I wrote back, “Thank you for your note. It fortifies me. I should print it out, fold it up tiny tiny, and eat it. And it’s funny (ha ha horror) because I was thinking about the debris / the lines / and how as I was writing this lecture the doctor found a dark spot inside my husband that needs to be biopsied, and then I started thinking about human tissue, and what do they even do with human tissue after it’s been biopsied, and how do we know what to keep and what to discard / and how will the boys and I live on this earth without him / and maybe we (our bodies) throw out so much of what we need, and maybe the stupid world does too. My great-aunt (a holocaust survivor) never threw out a single newspaper. Or a plastic bag. She said she was slapped by a Nazi as a baby and something froze inside her. I am writing this lecture and panicking about my husband and trying to stay calm for my boys and what I really want to do is throw out everything I own and keep everything all at the same time.”

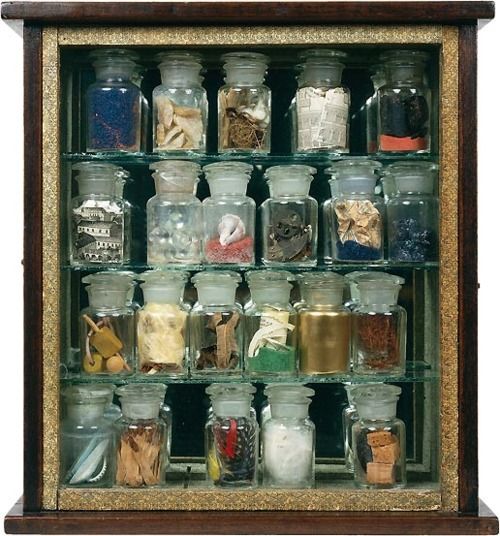

And also I was thinking a lot about this photo of an albatross. Its intestinal filled with marine debris. And then I began to think about how much it reminded me of Joseph Cornell’s “Pharmacy.” Colored sand, speckled shells, maps, newspaper clippings and cork live inside this miniature apothecary like medicine for the imagination. As I studied these two images it seemed almost impossible to differentiate between the poison and the pill, between the kill and the cure.

How do you negotiate the known and unknown in your work? I’m thinking in particular in the way in which your poems are tightly framed, sometimes by a particular word, definition, phrase, or action. They are restrained but also have a sense of expansiveness. How much do you know going into the writing, and what most guides you to the next word—sound, syntax, the idea, something else?

I usually follow a word or a name as far as it will take me, and somewhere along the line it will start to lose its feathers or skin or old shell or fur. Words really molt. You just need to be patient, and follow gently behind. Words are shy and cruel and beautiful and tender. I once followed a word all the way to a place called Mother, and by the time we got there we were both unrecognizable even to ourselves.

Do you go into working on a book having the idea first, or does the idea make itself known somewhere in the course of writing the poems? How important is narrative arc to your writing process?

I recently finished my first collection of stories, Everything Was Beautiful & Nothing Hurt, a collection of punctured fairytales filled with characters who are balanced right at the seam of the real and the unreal. There are, for example, a lot of characters on the telephone. Things happen in bars or hospitals or playgrounds. There are daycare centers and taxmen. But these real spaces don’t keep a cloud from bursting open and spilling out children. Or jokes from turning into men. Or a woman from getting pregnant by eating leaves stuck to a tin can. Or a king size bed from turning into a twin. Or a teacher from snowing. Which is to say, I’m experimenting right now with characters living in the present, while still maintaining what was at the center of my first two collections (of poetry): the absolute certainty of the unknowable.

I began the collection as a way to return to the I. Lucie Brock-Broido writes, “It is true that each self keeps a secret self that cannot speak when spoken to.” I wanted to start telling the secrets I was keeping from myself. An old friend once wrote to me about the cover of my collection Tsim Tsum. “I know you think you’re the girl on the cover, but really you’re the animal.” That note made me happy. Because I knew already I was the animal, and also I did not yet know.

What drew you to character, as opposed to a lyric I, or something more strictly persona? What can characters do for poems that the others cannot, if anything? How does giving something a name—a speaker, character, something else—help create meaning?

I think the different between persona and character is that persona is a mask the poet wears, whereas character is a mask the poet one wore, long ago, and lost, and now it’s covered in must and webs. It’s a mask that might’ve gone slightly rotten on one side, where maybe a small growth has begun to form. The job of the poet is to watch this growth, measure it, and give it a name. And slowly, slowly something resembling eyes and teeth will begin to poke through. Sometimes it takes seconds for a whole entire person to step into view, and other times years, and other times never. Other times all you ever get is an eye and a couple of teeth. Maybe a finger if you’re lucky. Maybe even a heart.

To what degree can you envision your characters? Can you visualize them, and is it important, do you think, for readers to be able to visualize them?

See above. Also, once I see them I see them everywhere I go.

You are a champion of the prose poem. What about the prose poem do you like most? Was there, for you, a time before the prose poem, or did you start there?

There was a time before the prose poem. I stood quietly in a field holding sticks. I knew I needed to either light a fire or build a house, but I wasn’t able to choose. The prose poem allowed me to do both and at the same time.

One of the poems I find most baffles my poet-friends, and one they also very often seem to go back to, is “The Departure.” It brings to mind the first poem of The Babies, “Day,” which begins “The world, in spite of everything, is very over.” When, in the process of writing Tsim Tsum, did you write the poem, “The Departure,” and why is it important that we begin Tsim Tsum there?

The Babies, my first collection, introduces Walter B. and Beatrice in a section called The Walter B. Interviews. They are two figures hatched at the center of ruin. When the book was done I began to miss Walter B. and Beatrice. I wanted them to return to me, but because they already were goners (so to speak) I needed to make for them a field, a field contingent on being gone, on galut (exile), and meet them there. This order is in keeping with the Kabbalist’s conception of redemption: first comes catastrophe, then, annihilation, and then comes tikkun or restoration. First there is the “forgetting of the Torah and the upsetting of all moral order to the point of dissolving the laws of nature,” and then there is repair. This is why the collection begins with goodbye.

In another interview you mentioned another project, the grandmothers, in which Beatrice and Walter B. reappear. Is this still in the works, and if so, can you tell us a little bit about it?

For a long time I have been working on a book called The Grandmothers. There is something wrong with it, but I haven’t yet figured out what. Beatrice visited for about a year and got so fed up she left. I mean, who could blame her? The book is about three children who come to live with The Grandmothers. There is a birthmark in the shape of a horse that wanders from one grandmother to another. And there is an incident with an overturned cake. This is the most I can say right now.

What are you working on now, and what’s on your personal reading list?

See above. And then see above again. Right now on my desk: The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington, James Allen Hall’s I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well, Robin Coste Lewis’s Voyage of the Sable Venus, Carmen Gimenez Smith’s Bring Down the Little Birds, Mary Ruefle’s My Private Property, Eileen Myles’ Inferno, Larry Levis’ Elegy, Deb Olin Unferth’s Wait Till You See Me Dance, and Samuel Beckett’s Molloy.

And I have to ask, are you willing to give up your trash?

At the last minute I have been known to give everything away.

To find out more about Sabrina Orah Mark, visit her website here, and find her work here

Read more about “live plants, corsages”

Listen to Sabrina Orah Mark’s Eleventh Hour lecture “The Poet as Collector”

Listen to her conversation with Rachel Zucker on the Commonplace Podcast

Mark currently offers poetry workshops in Athens, GA. See here for details.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies (Saturnalia Books, 2004) and Tsim Tsum (Saturnalia Books, 2009). Mark’s awards include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a fellowship from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, and a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award. Her poetry and stories most recently appear in Catapult, Tin House (Open Bar), American Short Fiction, jubilat, B O D Y, The Collagist, The Believer, and in the anthology My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales. She has taught at Agnes Scott College, University of Georgia, Rutgers University, University of Iowa, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Goldwater Hospital, and throughout the New York City and Iowa Public School Systems. She lives in Athens Georgia with her husband, Reginald McKnight, and their two sons. You can find her at www.sabrinaorahmark.com