by Nicola Koh

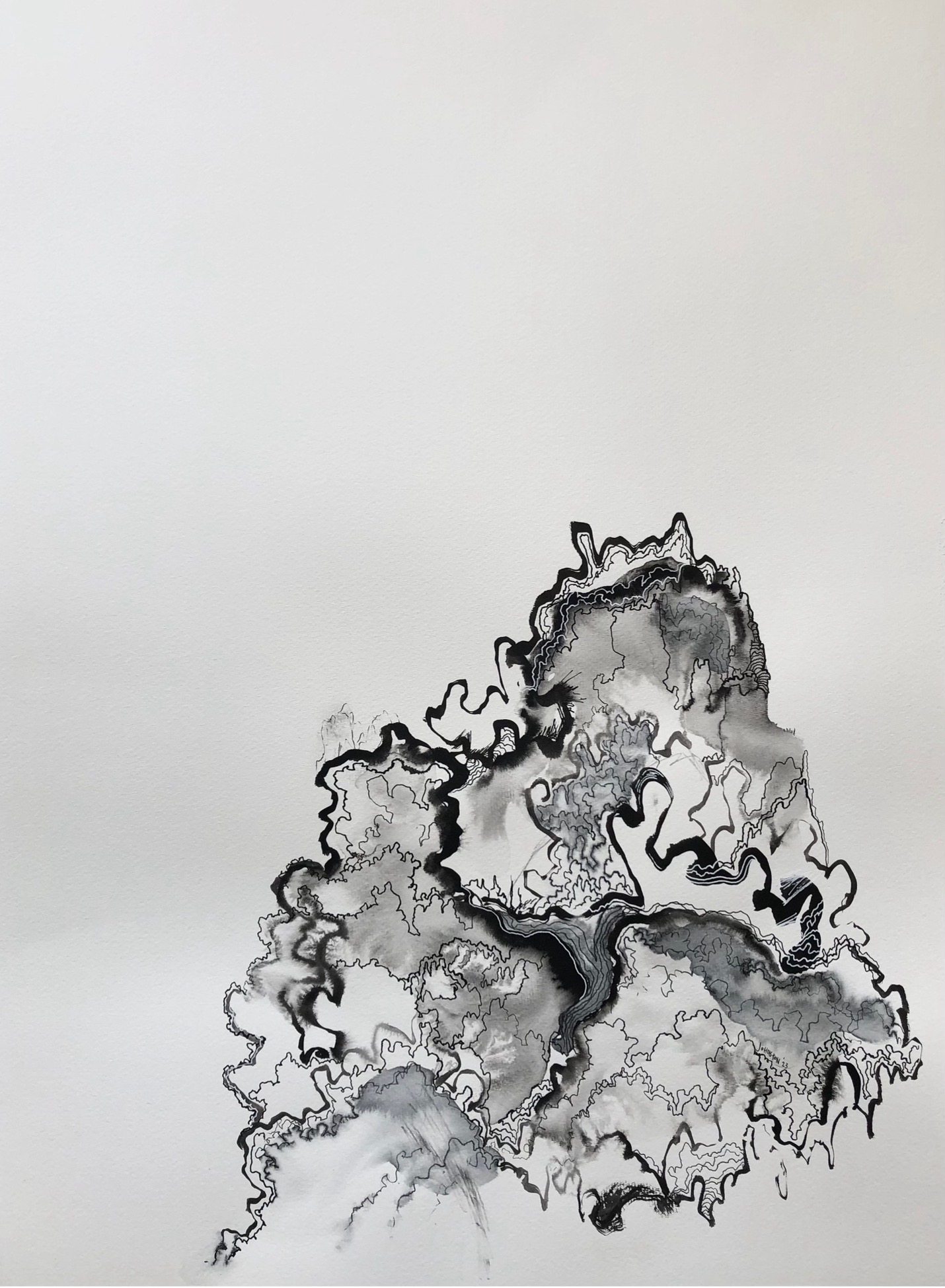

Topographia 6 by Jeff Johnston

I

Is it crazy to fall in love with a girl because of the way she said no?

Fall of 2010, our last year at Calvin College, I was keeping N company while she worked the student apartment desk, and I started talking about depression. It was something I’d seemed to be doing a lot, with a lot of different people, some barely more than Facebook friends. Like I was trawling for someone who would listen, actually listen, for that just one person who would know that in the end I’d been scared. But every time it felt like sympathy would dissolve to discomfort to all the platitudes I’d begun to collect—It gets better You’re stronger than this Have you tried Vitamin D I’ll never forgive you. The many polite ways to say goodbye.

But N wasn’t one for Midwestern Nice. She didn’t even wait for me to finish saying how sometimes it made sense to give up.

“No,” she said. “Don’t be stupid.”

She said no a lot. She dragged it, letting the word expand like bubblegum quivering in the air, then snapped it off.

We talked for an hour or more, but I was too dizzied to really pay attention. I couldn’t believe someone would hear all that and choose to be that blunt. I couldn’t believe someone would see all my brokenness and choose not to run.

Yeah, it’s stupid to fall in love with a girl because of the way she said no.

But I did.

II

I’m all about making up rules.

Don’t Kill Bugs

Always Include Tetris in Bios

Swipe Left on People with Shoeless Brown Children as Props on Tinder

Unfriend People on Facebook You Haven’t Interacted With in a Year or More

In 2016, I posted to N’s Facebook for her birthday, the only thing I’d said since her last. She didn’t even like the post. When my own birthday came, I combed through the wishes for something I knew wouldn’t be there.

Confession: sometimes I make rules to force myself to do something I don’t want to. I knew one day N would stop talking to me, but day-by-day-by-month-by-way-too-many-years I’d wait for a message, a post, a like. Clinging to these last vestiges, the social media ghost of all we’d been.

So I made a rule, because I knew that was the only way I’d be able to unfriend her. And even then, even after all those years, it felt like an asthma attack. Like I still couldn’t breathe without her.

III

Every few months I decide I’m over her. I go clubbing, try to flirt, go on online dates. Let sparks fly, let myself be buoyed in the rekindled hope and soar past the shadowed valley I’d been lost in for so long. And even when I taste another storm in the air, I’ll tell myself it’ll be okay this time—this time I’ll be able to push on, patch the tears, stop another new life from being ripped apart. This time, this time, Iwon’t end shattered on the ground.

It could be a case study in the cycles of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Except no one told me it’s not just one cycle, and it’s not just ten. And no one mentioned the greater cycle where the stages last years, moved imperceptibly but unstoppably by all the smaller ones I’d lose count of. That all those weeks staring at the ceiling, all the breakthroughs and rent hearts, all the times wounds broke open and all the times they healed—they were all just ticks in the long day of grief.

It’s been seven years, and I’m probably deep into the hours of depression now. I wonder if there is really a dawn coming. Can wounds like these really scab? Will these memories really start to blur, like files corrupted by too many transfers, college to seminary to leaving Grand Rapids for a state where every single place didn’t remind me of her?

Julian of Norwich, the Medieval Christian mystic, famously said: And it shall be well, and it shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well. Are those words of acceptance or denial? I suspect the answer is yes.

I’m tired of my ears perking when I hear her name. I’m sick of trying to force myself not to wake up from dreams she’s in, even when she’s just a cameo. I’m sick of how getting out of bed after those dreams still feels like leaving skin behind.

But then maybe some part of me prefers to let her haunt me.

Maybe I can’t stand all this love to be forgotten.

denial is buying a necklace online, all the way from Malaysia, the last Christmas of college, 2010, a black bowtie studded with diamonds anger is who the fuck buys a necklace for a person who chews out anyone who looks at her too long bargaining is we’ll find that one grand gesture that’ll blow her away, you’ll see depression is the first minutes of 2011, a bar with your family, and everyone else has someone to kiss, and you down abandoned glasses of champagne even though you’re already half-bottles deep in vodka and wine, and you wake up with vomit on your socks, and you’re so nauseous you don’t remember the thirty hours back to the States denial is the first morning back, tromping through knee-high snow to collect the package with the necklace, taking it out when your roommates are gone, holding it up to the light so it sparkles anger is she’s going to hate you, dipshit bargaining is we’ll figure it out, we’ll think of something, it’ll be perfect, it just has to depression is burying the necklace in your drawer and the sting whenever you run out of socks acceptance is giving the necklace away to a friend instead for her twenty-first birthday denial is Christmas 2012, Seattle, a vendor in Pike Place Market, the white stone necklace, grey-veined and copper-wire held, how you ask for the chain to be trimmed so it’ll glow between her collarbones

IV

The summer of 2010 was the best of my life. I drafted a novel for English Honors, over a hundred-thousand words, two-thousand a day, learning to type softly so I wouldn’t keep my roommate up into the a.m.’s. Friends took me to a bar when I turned twenty-one, and even though I didn’t get drunk, I still managed to pop two tires riding a curb hidden by curtains of rain. I memorised every world capital on a trivia website, explored Grand Rapids, discovered the term trigender and found it almost fit. When I finished the manuscript, I printed copies for teachers, friends, and family, with personalized dedications. One said, To N, for her honesty; she loved it. We hung with our mutual best friend, a trio of newly single Asians. We went to Lake Michigan, and N showed me she could drive with her legs folded on cruise-control. Later, sitting on the beach as the sun set, I mentioned I hadn’t seen a sunrise in a decade. She was scandalised and made me swear we’d see one together. Her shoulder nestled into mine, and the sand darkened to a harmony against her skin. And it was the best summer of my life. And it was the last I got to spend with her.

V

One day of 2011, our final winter at Calvin, N and I were in the atrium of the newly renovated Covenant Fine Arts Center, right outside the English Department, floor-to-ceiling windows and spiffy-yet-absurdly-comfortable sofas. N was so in love with it all, that she wrote a poem that was read for the dedication service for the building. It wasn’t very good, but she was the department darling, had the best grades of our class.

Do I sound jealous? She was jealous, too. Her GPA was point-one-four better, but I attempted more than anyone—over twenty classes with a Writing minor to boot. I was in every extracurricular and half of the pictures the department put up. She’d been too stressed out to complete Honors; I drafted a whole novel.

We were the crème de la crème, slogging away in the atrium while snow swirled outside, models of studiousness, a Korean and Malaysian showing the white kids how to English good. Except I was playing Tetris, and N decided to curl up next to me.

“I don’t know why,” she murmured as she fell asleep. “But I feel safe around you.”

N hated it when people needed her more than she needed them. She’d shun them until they got over it. But my masks are good. No one noticed the only time in college that I sat in the back of a class was Medieval Lit, next to her. Or how I positioned myself in Milton so I could see her reflection in the dimmed screen of my laptop. No one would have known that even though my asthma was being triggered by something in her perfume, I would never reach for my inhaler and risk waking her. That I wouldn’t move even when I started running late for a meeting. That I couldn’t stop sneaking glances at a face I’d already memorised: moles below her right eye and above her lips, mangosteen lips and a grin that uncovered gums and upper teeth, eyes like twin suns peeking over a horizon.

An hour later, she was stretching like a cat. “You let me sleep that long?”

I said I didn’t have anywhere to go, hiding my choked breath, waiting till she was out of sight to rummage for my inhaler; just so she wouldn’t realise I’d suffocate before I left her.

Because she felt safe around me.

VI

There was a picture on her blog of us on graduation day, the 21st of May, 2011. I don’t know if it’s still there: the privacy settings having long been limited to a circle I’m no longer a part of. We’re in full regalia, but N’s unzipped hers to reveal a yellow sun dress, hemmed with red carnations. I’m wearing my Honors medallion, singular, even though I’d earned Honors in Religion too, even though I’d almost, literally, killed myself getting double Honors only to find out the cheap Dutch-American bastards still only gave out one medallion.

In the picture, N’s biting my medallion. The caption reads: Okay, I’m a little jealous.

For months before graduation, some crackpot pastor had been saying the world would end that very day. Us seniors laughed about it a lot, but secretly we were just a little nervous that Jesus would, in fact, crash the party. I said I’d yell at him to go back. I was only half-joking. The Kingdom of God could fucking wait. I was going to graduate. I’d wear that damn medallion. N would be jealous. Jealousy is not love, but it’s something.

I hoped it could be something.

denial is you get your hair cut even though you want to grow it out because N likes it short, because N is straight, because N wouldn’t want you as a woman, because even though you haven’t heard from her in months, she’s definitely going to care about your latest haircut anger is fuck it, buy 30-gallon bag’s worth of women’s clothes from Goodwill, let a Bobbi Brown rep scam hundreds of dollars of makeup onto you, skip seminary homework, dress up, start hormone replacement therapy, drive to the Motor City Tattoo convention for a tattoo of a naked female angel to celebrate transitioning bargaining is think, think, think, how do we get N to love a woman depression is no one thinks you’re a woman, and N will never love you, and it turns out your chosen method of suicide is much harder than it sounds acceptance is stop giving a fuck what people think, you don’t need hormones and clothes and makeup to be who you are, this is a new chapter, you can get a haircut not because N likes it short but because you want to, because you’re finally okay that N doesn’t love you, it’s okay if N will never love you, she will never ever love you, what’s the point of a life where N will never love you

VII

This is the first time we met.

It’s the second morning of international student orientation, and I’m one decent sleep from a thirty-three hour journey from Malaysia to the States and a four-hour car ride from Chicago to Michigan at midnight after a storm grounds all flights. By the time I get to breakfast, there’s just cereal left, and the only stragglers are a Korean girl and father, a missionary family from Tanzania. I sit kitty corner from them on a long table, and the father and I nod hello. N’s pissed there’s no soy milk. Her father says something in Korean, and she snaps back that she’s vegan, remember? I look at my bowl and think, one of those.

Even though we accrue many mutual friends, we don’t really talk until the end of the first year in a group study session. She asks if someone will test her for Art History, and I volunteer out of boredom. We go into the dorm prayer room, which is really the dorm hookup room, and so it feels a little scandalous with both of us dating other people that I’m suddenly struck by how pretty she is. And it floors her when I begin to memorize her flash cards, and it floors me she’d be impressed, she’s so ferociously intelligent.

That summer, she invites me to hang out with the other Asians. When school starts, she loves when I play classical guitar for her in her dorm room. We watch Moulin Rouge together, and she tells me not to make fun, and I don’t. I also don’t say how nice it feels to lie beside her, stomachs on carpet, and how during all the love songs it seems like maybe her shoulder dips just a little into mine.

She studies in England of junior year, and one day I get a postcard with a picture of a clock tower in York, her tiny handwriting curling round the margins. Bet you didn’t expect to get this? That spring, I flabbergast her when I say I can’t cry unless someone I love dies. A few days later my grandfather does in fact die. I don’t cry, but N hugs me anyway.

She starts wanting to see all my writing, like the surprisingly popular column in the school newspaper I create called “Animals That Will Blow Your [Fucking] Mind.” Sometimes I write these in her apartment while she studies an hour or two, and she can’t believe I can write that well that fast. She tells me that a piece I wrote on depression for Creative Nonfiction felt like it named her own experiences.

By the end of December, I’m spending ten hours preparing a group presentation on Julian of Norwich just to impress her. By January, I’m running across campus during a play’s intermission to get her a Snickers because she was hungry.

I was the first person she told about her one-night stand, the first time she’d had sex since she’d been dumped. She lay on the carpet while I asked all the right questions and said all the right things. Eventually she wiped away some tears and thanked me for listening, and I said I’d always be there for her. Then I went back home and stared at the ceiling just like she had.

And one night, late in February, I was at the apartment desk again, talking about depression. But this time it was less a rant than a confession because all I felt was tired. And this time she didn’t say no. She hugged me and kissed me on the shoulder.

Then came the annual English Winter writing retreat. The one where I would hide between two mattresses so no one would make me go to group activities where I’d get so depressed I’d want to run away, because I could feel my masks crumbling. Like when on the bus over, when we’d been told to write funny haikus, she’d turned around from the seat in front and said, “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours.” When I stopped by her room to talk with her and another student, and the tension was palpable. When I couldn’t stop glancing at her because I didn’t know how long I had to look at her face.

She confronted me after we got back, and I told her I was fine being friends if that was all she wanted. But I worried I hadn’t been convincing in person and sent a follow-up email. I thought I was so much clearer, so persuasive, in writing. I thought she’d laugh at clever jokes like I would cut my arm off for you, except I like my arms. She stopped talking to me instead.

All the while I was getting more depressed than I’d ever been, and most days I counted it good if I was semi-presentable and only a few minutes late to class. I stopped dimming my laptop in Milton so I wouldn’t have to see N studiously ignore me because she thought I was doing it for attention.

Spring Break, after all my roommates had left, I played Tetris for hours. I told myself if I broke a million points I was allowed to die, but the power tripped right after I did. It felt like a sign from God, and it felt like cosmic betrayal. Soon after school restarted, I woke up to a chorus of voices my head demanding why I hadn’t killed myself. I stopped going to class. I tried to stay around friends as often as I could, and they all seemed to take shifts because I was rarely alone.

But N still wouldn’t look at me, still thought I was being melodramatic, and after two weeks I couldn’t take it anymore. I wrote another email, but this time ran it by my roommate. I told her I wasn’t trying to get her to like me, I was really doing that badly. I said I didn’t want to go with us fighting. She called me, and we made up.

But I knew our friendship was one jolt from shattering. So I let her be the one to invite me to hang out, in groups. I gave away the necklace I had bought her. Once when I was telling our friend how I preferred when women wore no makeup, N snapped from the couch, “I wear so much makeup, so why do you…” Her lips tightened. “Never mind.” And I changed the subject.

I didn’t act delirious when she invited me to light sky lanterns with the other graduating Asians. I didn’t return her excited hug too deeply or for too long. I didn’t stare at her face shining as those dozen lanterns were swallowed into the dark, like vanishing suns.

denial is the dreams where she lets you hold her denial is the dreams where she forgives you and wants to be friends denial is the dreams where she invites you to a party with all your friends, the dreams where you run into each other and small talk and she wishes you well depression is the dream where you think of sending an email asking to be friends, but you decide against it because you don’t think she’d reply depression is even in your wildest dreams you can’t believe she’d even email you back denial is surely you must matter to her, surely she’d say something, anything at all depression is you wouldn’t be able to handle what she had to say depression is you want to send the email depression is you want to not survive the reply

VIII

After we graduated, we exchanged sprawling emails. She’d talk about travelling Europe, starting a library in the Tanzanian town she’d grown up in, applying to Oxford for a PhD in English. I’d talk about Seminary, hypocrites, trying to memorise Romans, and the latest thing my puppy had eaten. She wrote every two weeks or so, and I made sure not to reply for at least three days (Don’t Look Desperate, Stupid). I starred the emails, and every couple of months, I’d read them all again. She signed each one, “love, N.” And I knew I shouldn’t read anything into it, but it still made me happy.

In 2013, she was coming to Grand Rapids for her sister’s graduation and staying for the summer. She began suggesting more and more things we should do. As the months dwindled, her proposed plans became more elaborate, and her tone became giddy.

I let myself pretend. I composed a song for classical guitar, and she loved it, but I didn’t tell her I wrote it for her. I watched a sunrise on the biggest lake in Grand Rapids and told her it was as beautiful as she’d promised, and I wanted so badly to tell her how much it ached that she hadn’t been there.

And one day, during Systematic Theology II, I sent an email.

—Je pense que je t’aime.

She was relearning French, but still made me translate.

I think I like you.

She wrote back. —Do you really want to do this again?

That summer she was in Grand Rapids six weeks before she even asked to see me. I came to the coffee shop in a yellow plaid shirt and red jeans, small amounts of makeup. She said my chin looked orange. I informed her the internet said to apply orange makeup to cover up the blue-green tinge of a shaven beard (advice I now realise only applies to white skin). She said I needed more practice, but when she went to the bathroom, she said I looked like a woman from the back, and that made me happy.

We hugged outside. I knew she wouldn’t want me to look back at her, so I didn’t. I told myself everything was going to be okay, that we’d see each other again. I wish I’d turned around. To look at her just one more time.

But I couldn’t accept that “love, N” could be just another way to say goodbye.

depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression is this love is depression

IX

In 2014, a therapist asked me to give N a score on traits like strength, intelligence, and charisma. I scored her compassion at 4. I gave her 9s and 10s for everything else.

“Wow,” he said. “She must really be something.”

He gave the best explanation for why it was so hard to let go. I’d started falling for her in the middle of my first suicidal episode, and my emotional defences had been too devastated to stop feelings for her penetrating into my deepest self. Like an infection gone bone deep.

X

You know, sometimes your face comes up pixelated.

I think about how somewhere in the world you’re happy and popping egos and impressing everyone, and sometimes it makes me smile.

Is it acceptance to learn that we try, fail, and still go on? Wounds turn to scars turn to new skin that can break from new wounds. Bit-by-bit, cell-by-cell, we are shed, every breath the first of a new life and the last of another. The tissue connecting present, past, and future snapping one strand after another, what is turns into what was and what could be becomes what isn’t.

Bodies crumble, and the world forgets everyone who’s ever lived. And for all my vaunted memory, I’m forgetting too. Sometimes the me that fell in love with you feels almost like a friend I’ve lost touch with. Sometimes I can’t hear the way you said no.

Is the heart’s ability to heal from the worst wounds its most miraculous or its cruelest?

The you that I loved has been folded into all these years you’ve lived without me, and all that remains of us is all this love.

One day even that will pass. But you know what? It’s going to be okay. It’s going to be okay.

Everything’s going to be okay.

XI

Right?

Nicola Koh is a Malaysian Eurasian 16 years in the American Midwest, an atheist who lost their faith completing their Masters of Theology, and a minor god of Tetris. They got their MFA from Hamline University and were a 2018 VONA/Voices and 2019/20 Loft Mentors Series fellow. Their nonfiction has appeared in Crab Orchard Review, Sweet: A Literary Confection, and others. They enjoy taking too many pictures of their animal frenemies, crafting puns, and listening to public domain audio books after injuring their neck reading (which she consoled herself by calling a literary wound of honour). See more at nicolakoh.com.

Jeff B. Johnston was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma. After earning his BFA at the University of Tulsa, Jeff has exhibited and performed in Tulsa, Kansas City, Mufreesboro, Memphis, Baltimore, Arlington, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, Oakland, Berkeley and San Francisco. In 2016, Jeff earned his MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute. Jeff continues to exhibit 2D work, performances, and films around the San Francisco Bay Area.